Degree attainment by socioeconomic background: UK, 2017/18 to 2020/21

Ad-hoc experimental statistics

This statistical bulletin includes: Key findings | Introduction | Findings | Concluding remarks | Notes

Key findings

- Between the academic years 2017/18 and 2020/21, degree attainment levels (which we define as the proportion of first degree qualifiers being awarded a first or upper second) were highest in Northern Ireland and lowest in Wales.

- At a UK-wide level, the disparities in degree attainment between those from the most and least deprived areas (based on HESA’s deprivation measure) has narrowed by approximately 2 percentage points during COVID-19 (i.e. the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21).

- However, this finding is driven by provision in England, which accounts for 87% of our sample.

- In Wales, differences in degree attainment between the most and least deprived deciles has widened slightly since the pandemic began.

- In contrast, both Scotland and Northern Ireland have experienced greater reductions in the gap – primarily as a result of improving degree attainment among those in the most deprived decile.

- The difference in degree attainment between those from the most and least deprived deciles has gone down in Scotland from 17 percentage points to 12 percentage points.

- Northern Ireland has experienced a similar decrease, with the gap going from 14 percentage points before the emergence of COVID-19 to 9 percentage points during the pandemic.

- Based on analysis of the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21, we find that the gap between the most and least deprived deciles is now widest in Wales. Prior to the pandemic (i.e. in the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19), the largest difference was observed in England.

Introduction

Over the past few years, HESA has been developing a new UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation. Alongside having the potential to enhance our official statistics, one of the primary benefits of such a variable is that it may enable comparisons to be made across the four nations, which is not possible with existing area-based measures such as the Indices of Deprivation. The Office for Statistics Regulation notes that data based on new fields should firstly be released as experimental official statistics, with users offered an opportunity to feedback on the value of the output. As part of this circulation, we have therefore provided information on how our readers can supply us with their comments and we would particularly appreciate user thoughts on matters such as whether they would like statistics of this kind to be disseminated on an annual basis (e.g. through our student statistical bulletin or accompanying open data release). The exact period that our new measure will remain an experimental statistic will depend on the views we receive from users on its relevance, as well as factors such as the stability of the methodology. Our current expectation is that the experimental label will be in place for one to two years.

This study supplies experimental statistics on the association between degree attainment (i.e. the proportion of first degree qualifiers awarded a first or upper second class) and our area-based measure of deprivation across the UK. Social mobility is often viewed as relating to the extent to which an individual’s outcomes (e.g. on the basis of earnings or employment) differ to that of their parents.[1] Improving social mobility continues to be a key policy objective across all nations of the UK, with education seen as one of the potential ways in which this can be achieved. Consequently, this has led to regular statistics being distributed on attainment gaps in primary and secondary education by various measures of deprivation. The evidence consistently illustrates those experiencing greater levels of deprivation display lower levels of attainment, which can inhibit progress in raising social mobility.[2]

Following the COVID-19 pandemic and the interruption this had on the delivery of education, there has been plenty of research looking at how gaps in school attainment by socioeconomic background have altered since 2020.[3] However, in higher education, while much attention has been paid to the trend in the proportion of graduates being awarded a first or upper second[4], there has yet to be any UK-wide analysis of whether socioeconomic gaps in degree attainment have shifted since the start of COVID-19 to the best of our knowledge.[5] This is an important matter to consider from a social mobility perspective, as degree attainment is correlated with access to jobs and future earnings.[6] Addressing this matter is the principal purpose of this work. The following questions will be examined as part of this publication (both for the UK as a whole and by nation);

- How do degree attainment levels compare between those from the most and least deprived areas?

- Has there been a change in the extent of the gap since the pandemic?

It is important to note from the outset that we are looking at the correlation between degree attainment, deprivation and the pandemic. As we cannot assess the role of other factors that may have influenced the gap over time through our data, the exploration we carry out will not enable us to conclude to what extent COVID-19 caused any change in the level of disparity that we observe.

The sample we draw upon for our analysis consists of UK-domiciled full-time first degree students who began their programme of study at the age of 18, 19 or 20 and subsequently qualified in any of the academic years between 2017/18 to 2020/21.[7] Individuals with unclassified degrees are excluded from the investigation. We also do not include those who studied in further education colleges within England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as we do not currently hold this data within our administrative records.[8] Those who completed their course in either 2017/18 or 2018/19 will not have had any disruption to their learning/assessment as a result of COVID-19, while those who graduated in 2019/20 or 2020/21 will have experienced changes in the delivery of their programme.[9]

Findings

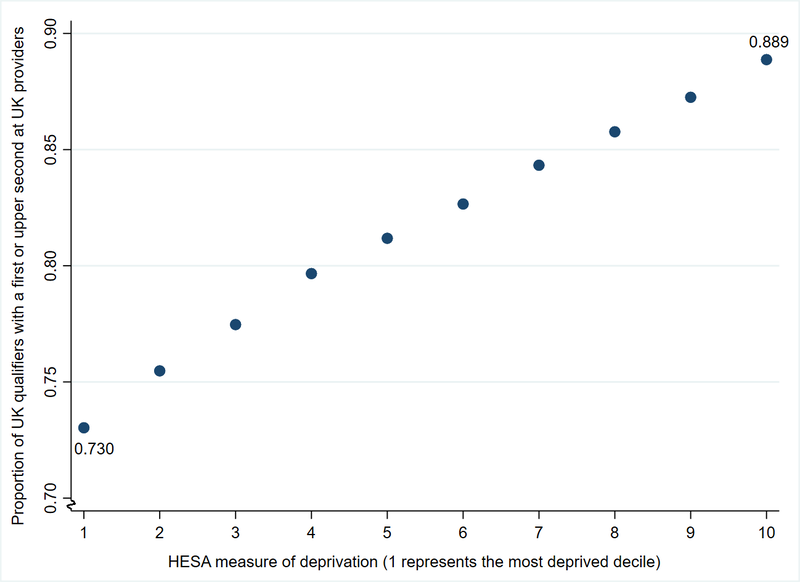

Beginning with the entire sample, Figure 1 shows how the proportion of qualifiers that were awarded a first or an upper second varies by our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation. A linear correlation is evident, with attainment rising as we move from decile 1 to decile 10. The gap in degree attainment between those in the most and least deprived deciles stands at 16 percentage points. Previous research that has explored the potential reasons behind this pattern has suggested that prior (school) attainment could be a key factor in understanding why these discrepancies exist, though it is important to note that this study was limited to England and utilised a measure of socioeconomic deprivation that combined individual and area-based measures.[10]

Figure 1: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation among those who qualified between the academic years 2017/18 – 2020/21. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20.Download data for Figure 1 (CSV)

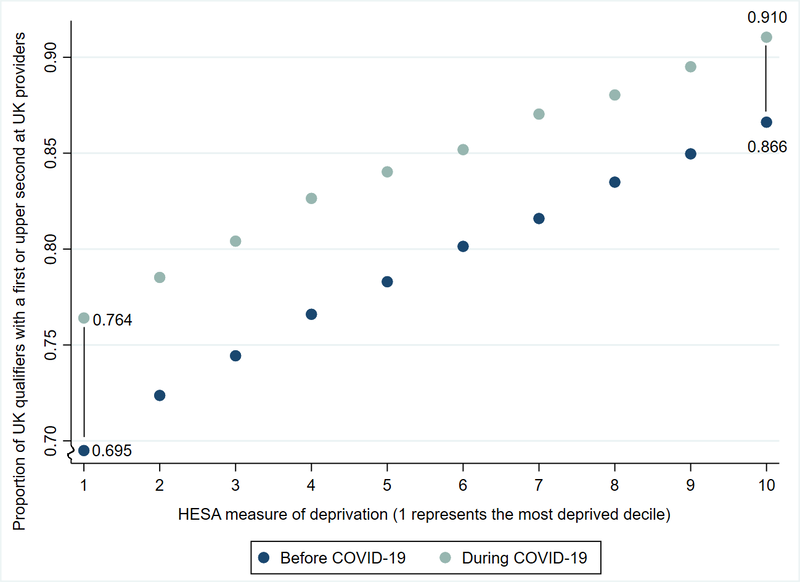

In Figure 2, we partition our sample based on whether or not an individual qualified in a year hit by the pandemic. In our student bulletin released in early 2023, Figure 16 illustrated that the proportion of UK-domiciled full-time qualifiers awarded a first or upper second rose by around 5 to 6 percentage points during the COVID-19 period – with this driven by a rising proportion of first class degrees.[11] A glance at Figure 2 suggests that decile 1 has experienced a larger change in comparison to decile 10, resulting in a decrease in the gap between decile 1 and decile 10 of a few percentage points.

Figure 2: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before and during the COVID-19 period. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20. The before COVID-19 period covers the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19, while during COVID-19 incorporates the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21.Download data for Figure 2 (CSV)

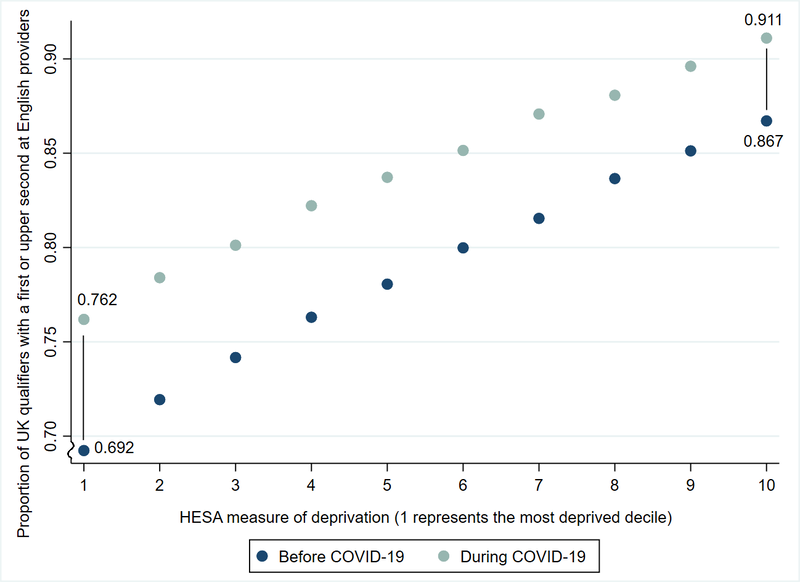

Looking at the distribution of qualifiers by country of provider, 87% are based in England. Indeed, carrying out the above analysis for England only (Figure 3) leads to essentially the same conclusion we see for the UK as a whole. That is, there has been a decrease in the gap of just under 3 percentage points between the most and least deprived deciles during COVID-19.

Figure 3: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before and during the COVID-19 period. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who studied at an English higher education provider and started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20. The before COVID-19 period covers the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19, while during COVID-19 incorporates the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21.Download data for Figure 3 (CSV)

However, with one country accounting for such a large proportion of higher education provision, there is the possibility that other nations of the UK are experiencing different trends to those seen in England. It is this issue that we now focus on and we begin by examining providers in Wales.

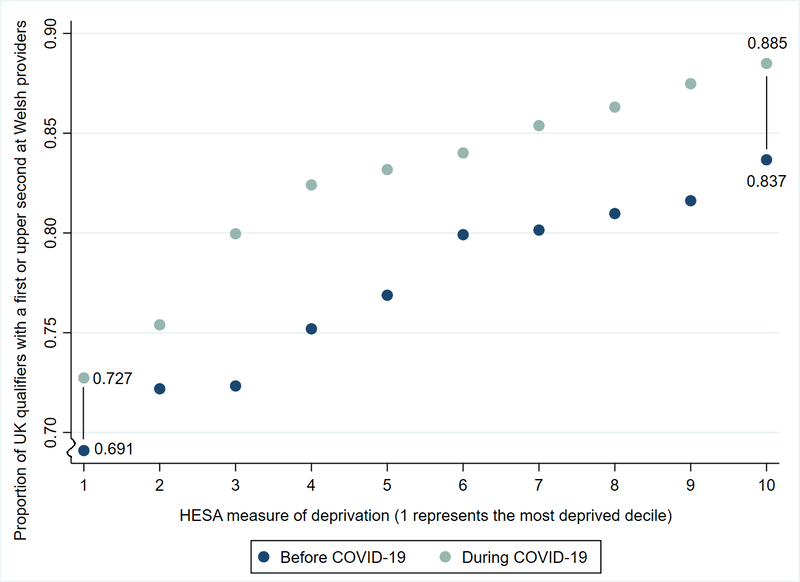

Figure 4 highlights an alternative story developing in this nation. Here, the difference in degree attainment between the most and least deprived deciles has increased slightly following the COVID-19 outbreak. The largest movements seem to have occurred in deciles 3 and 4, resulting in a change in the overall pattern that we observe between attainment and deprivation. Following COVID-19, we see a steady downward trend in the percentage awarded a first or upper second as we go from decile 10 to decile 3, though a greater decrease then arises from this point onwards.

Figure 4: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before and during the COVID-19 period. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who studied at a Welsh higher education provider and started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20. The before COVID-19 period covers the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19, while during COVID-19 incorporates the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21.Download data for Figure 4 (CSV)

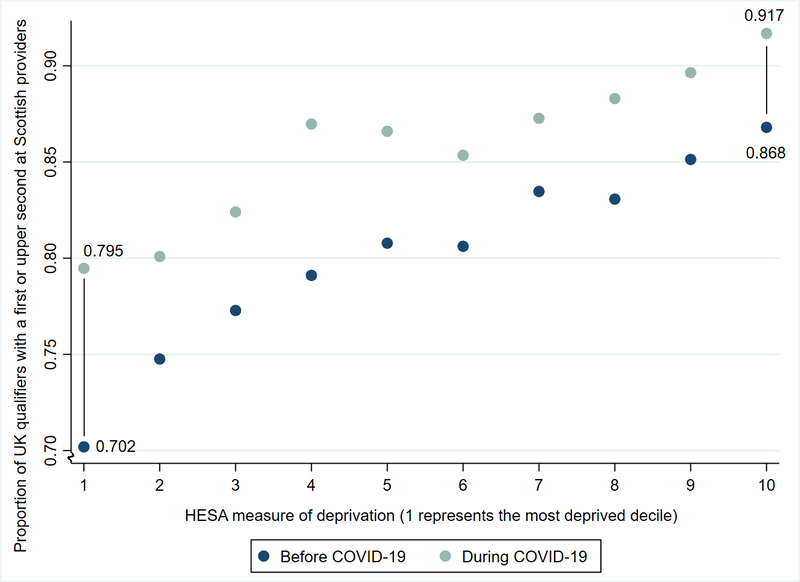

Within Scotland, prior to the start of COVID-19, the difference in degree attainment between the most and least deprived deciles stood at 17 percentage points. However, since 2019/20, there has been a greater increase in the proportion of qualifiers in decile 1 being awarded a first or upper second, with this value having gone up by 9 percentage points. In contrast, a smaller upward trend is seen among those from the least deprived decile. The overall consequence of this is that the disparity in degree attainment has now gone down to 12 percentage points.

Figure 5: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before and during the COVID-19 period. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who studied at a Scottish higher education provider and started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20. The before COVID-19 period covers the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19, while during COVID-19 incorporates the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21.Download data for Figure 5 (CSV)

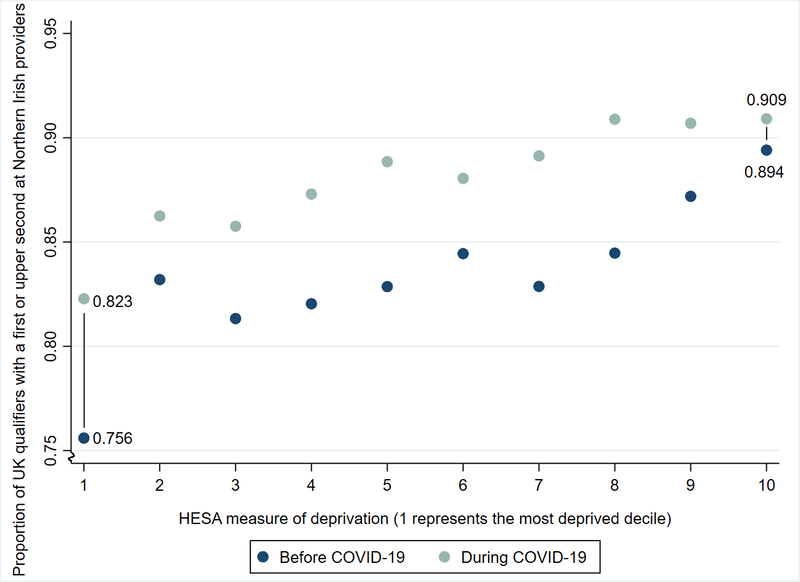

Similarly in Northern Ireland, the changes in the level of degree attainment following COVID-19 have not been even across the deciles of deprivation. In decile 10, the proportion awarded a first or upper second has barely shifted, while an increase of almost 7 percentage points is witnessed among those falling into decile 1. As in Scotland, the result of these trends is a decrease in the gap in degree attainment between the most and least deprived deciles, with the difference currently at around 9 percentage points – having been approximately 14 percentage points before the pandemic.

Figure 6: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before and during the COVID-19 period. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who studied at a Northern Irish higher education provider and started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20. The before COVID-19 period covers the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19, while during COVID-19 incorporates the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21.Download data for Figure 6 (CSV)

Concluding remarks

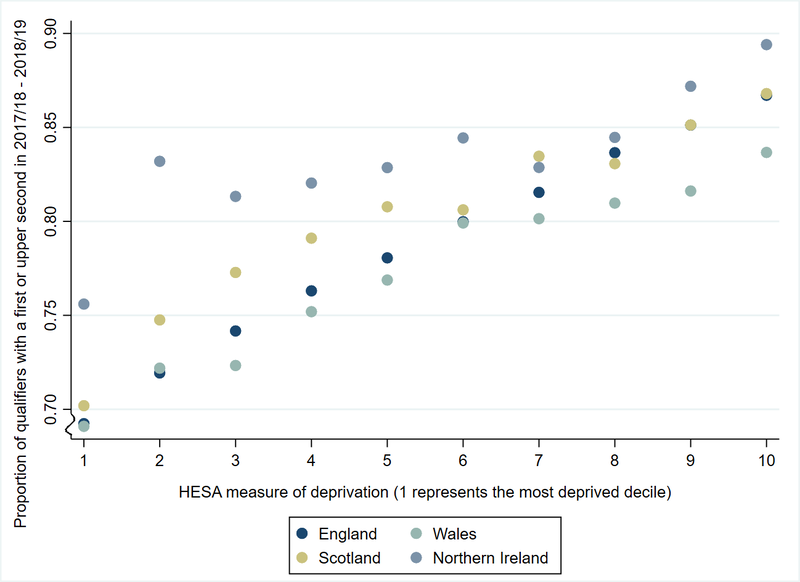

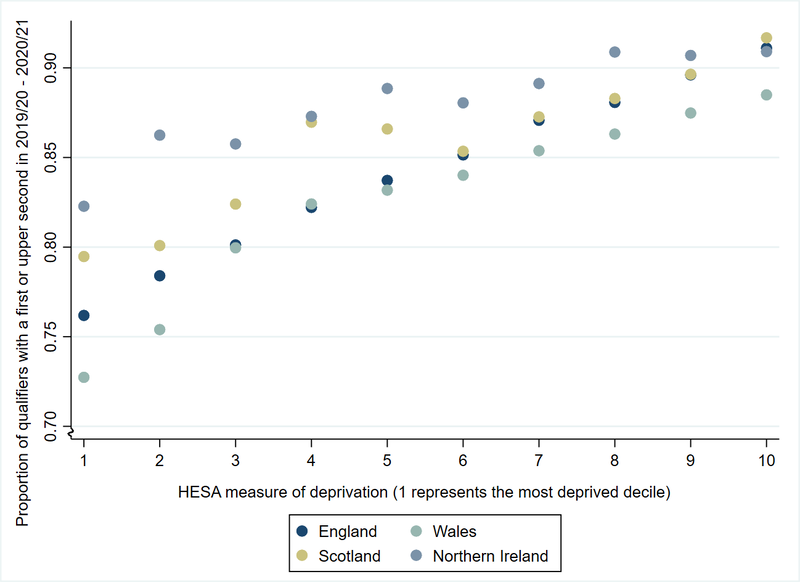

It is perhaps useful to end by again looking at the UK-wide picture – both before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. From Figures 7 and 8, we see that across the majority of deciles, degree attainment levels tend to be lowest in Wales and highest in Northern Ireland. Prior to COVID-19, degree attainment levels among those in the most deprived decile were quite similar in Scotland, England and Wales. However, as a result of the larger increases in degree attainment we have seen among qualifiers in decile 1 who studied at Scottish providers in our sample, we now observe a more noticeable difference in the degree attainment levels of those from the most deprived decile across the four nations.

What we are unable to ascertain from HESA data is the reasons behind why these movements have occurred in the four nations. While administrative records have the benefit of providing huge quantities of data, the number of variables available to the analyst tend to be limited. Exploration of why these trends have happened would therefore likely require rich survey data and/or qualitative studies relating to the higher education experience for students across the four nations. Future work in this area may wish to use data from more recent academic years to examine whether the patterns that have been found in this piece alter in any way among the latest cohorts of students.[12]

Figure 7: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation before the emergence of COVID-19 by country of provider. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20 and qualified in either 2017/18 or 2018/19.Download data for Figure 7 (CSV)

Figure 8: The association between degree attainment and our UK-wide area-based measure of deprivation during the COVID-19 period by country of provider. The sample is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first degree qualifiers who started their degree at the age of 18, 19 or 20 and qualified in either 2019/20 or 2020/21.Download data for Figure 8 (CSV)

Notes

[1] See, for example, page 13 of https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1084566/

State_of_the_Nation_2022_A_fresh_approach_to_social_mobility.pdf

[2] See, for example, https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/ECYP/2022/8/2/c33c7780-50fe-47d8-99fc-84807b85f2df#86f70af6-a1be-4c7b-925a-adc38ed46dbc.dita, https://www.gov.wales/wellbeing-wales-2022-children-and-young-peoples-wellbeing-more-equal-wales-html, https://www.niauditoffice.gov.uk/files/niauditoffice/media-files/249503%20NIAO%20Closing%20the%20Gap%20report%20Final%20WEB.pdf and https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/documents/support-for-schools/bitesize-support/EEF_Attainment_Gap_Report_2018_-_print.pdf?v=1679364214

[3] See, for example, https://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Covid19_2021_Disadvantage_Gaps_in_England.pdf, https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/new-research-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-disadvantage-gap-in-primary-schools and https://www.gov.scot/publications/achievement-curriculum-excellence-cfe-levels-2020-21/pages/5/

[4] See, for example, https://www.ft.com/content/334bbc66-3ccb-4f6c-986b-a8d46f3801b0 and

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/ofs-opens-grade-inflation-investigations-three-providers

[5] There are examples of nation-specific outputs looking at the gap in degree attainment by socioeconomic deprivation. For example, the Office for Students publish data using the English Index of Multiple Deprivation. Using this different area-based measure and based on a quintile analysis, they find a narrowing of the gap in degree attainment between qualifiers in quintile 5 and quintile 1 in the academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21 (i.e. the first two years in which study was disrupted by the pandemic). Further information can be found at https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/.

[7] As this is not a statutory statistical release designated under the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 in England, the dataset we use includes only those higher education providers that agreed for data they had submitted to be used for research purposes [see Categories of Onward Use (category 1) for further details].

[8] HESA are looking to address this gap in our data through the College HE project. Further information can be found at https://www.hesa.ac.uk/innovation/college-he.

[9] In our data, academic year refers to the year in which the qualification was reported to have been awarded to HESA. In some instances, this may not necessarily be the same as the year in which the individual completed their qualification (e.g. the student may have gained the qualification at an earlier time, with the data relating to this submitted retrospectively by the provider).

[11] https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/19-01-2023/sb265-higher-education-student-statistics/qualifications. It should be noted that due to the pandemic, many providers issued public statements that a 'no detriment' approach would be adopted when it came to assessment in 2019/20. This typically ensured that students would be awarded a final grade no lower than the most recent provider evaluation of their attainment. With the 2020/21 academic year still subject to pandemic-related disruptions, many providers continued to implement mitigation or ‘no detriment policies’ designed to take into consideration the ongoing difficulties faced by students.

[12] In England, the Office for Students have recently illustrated that the gap in degree attainment, based on comparisons of qualifiers in IMD quintile 5 to those in quintile 1, widened in 2021/22. See https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/fa35219d-c363-40a9-9b85-d618ae27da1c/access-and-participation-data-findings-from-the-data.pdf for further details.

Release date

18 April 2023, 9:30

Coverage

UK

Release frequency

Ad-hoc

Themes

Children, education and skills

Issued by

HESA, part of Jisc, 95 Promenade, Cheltenham, GL50 1HZ

Press enquiries

+44 (0) 1242 388 513 (option 6), [email protected]

Public enquiries

+44 (0) 1242 388 513 (option 2), [email protected]

Authors

Tej Nathwani,

Alex Lastoria-Butler,

Stephanie McLean

Feedback

Please email comments, suggestions and questions to [email protected].