Adding value to UK graduate labour market statistics: The creation of a non-financial composite measure of job quality - Section 4: Wellbeing and employment

Section 4: Exploring associations with subjective wellbeing and ‘highly skilled’ employment

One of the distinctive features of the Graduate Outcomes questionnaire is that it contains sections on earnings, job quality indicators relating to the design and nature of work, as well as subjective wellbeing. As noted in the introduction to the paper, one would expect job quality variables to be associated with worker wellbeing. Our survey on early career graduates therefore provides us with the unique opportunity to examine how earnings and our composite measure correlate with wellbeing.

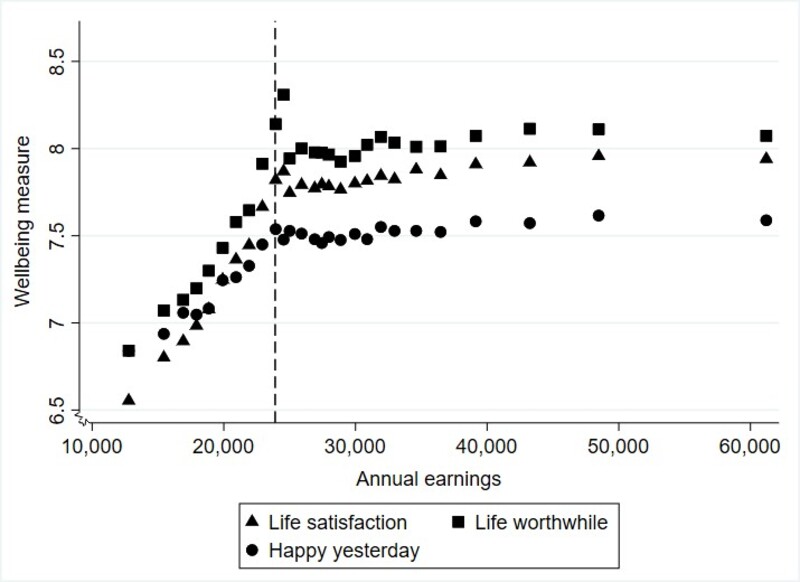

Figure 1 below illustrates the correlation between earnings and wellbeing (salary information is trimmed at both the top and bottom of the distribution to remove outliers/values that are likely to have been misreported). The first thing we observe is that a positive association between earnings and wellbeing is only seen until we reach an annual salary of approximately £24,000. Thereafter, the relationship flatlines.

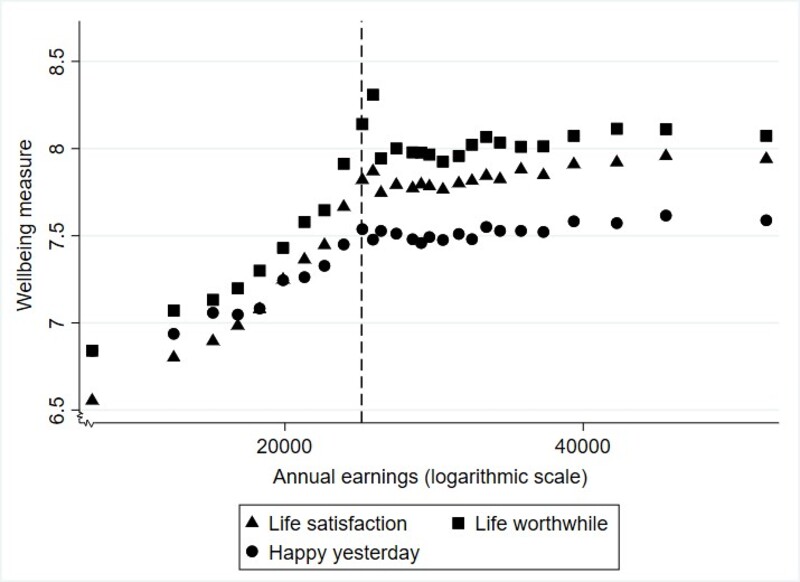

In his study on income and wellbeing around the world, Deaton (2007) illustrates how the relationship between GDP per capita and life satisfaction changes when a log transformation is applied to the former variable. That is, a linear association exists between the logarithm of GDP per capita and life satisfaction, while a concave function emerges in the scenario where we utilise the original GDP information. One of the potential criticisms of Figure 1 therefore is that we are looking at income in absolute terms rather than concentrating on percentage changes (Deaton and Kahneman, 2010). Yet, in our data, regardless of whether it is in its logarithmic form or not, income only appears to be positively related with happiness and the extent to which life is worthwhile/satisfying to a certain point before further increases are no longer associated with additional changes to wellbeing (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The association between annual earnings in pounds sterling and wellbeing among our graduate sample.

Figure 2: The association between annual earnings in pounds sterling (logarithmic scale) and wellbeing among our graduate sample.

Given the conclusions of Deaton and Kahneman (2010) that ‘high income buys life satisfaction’, the results we present here may seem puzzling. However, Cheung and Lucas (2015) examine whether the link between these two variables may vary by age and note that the relationship is weaker among younger adults. As most individuals in the UK enter higher education between the ages of 18 and 25 (hence generally qualifying while they are still in their twenties), our sample predominantly comprises of those in this age range. This could therefore potentially explain the results we observe between income and wellbeing, with the examination of this association at a later point in the careers of graduates being a potentially fruitful area for future research. Based on the evidence presented here though, the lack of a clear correlation between income and wellbeing beyond a certain earnings threshold does suggest that it would be valuable to consider a broader set of indicators for graduates. Annual earnings alone will not necessarily proxy for their non-monetary outcomes, which are increasingly recognised as being important to study when evaluating societal and individual progress (Stiglitz et al. 2009).

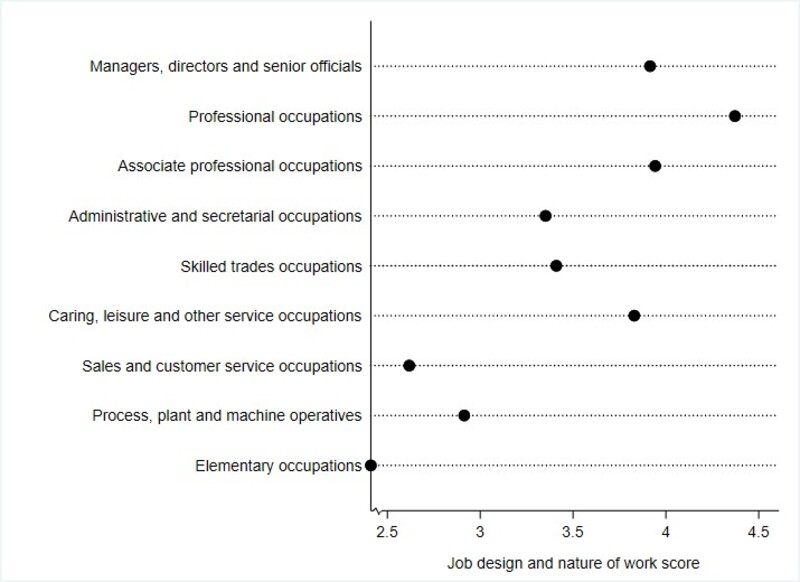

Figure 3 highlights the association between our design and nature of work dimension (a non-monetary measure) and subjective wellbeing. Here, a linear and positive pattern is seen between this component of job quality and three wellbeing measures. Helliwell and Wang (2011) state that our life evaluations (e.g. our satisfaction with life and the extent to which we believe it is worthwhile) are more likely to be influenced by our wider social and economic circumstances, while emotions (e.g. happiness) have a higher probability of being determined by the short-term conditions we experience (e.g. whether it is a weekend or weekday). The graph shows that a steeper gradient exists for the life evaluation variables when compared with happiness, which provides support to this view, since work forms a fundamental part of our lives.

Figure 3: The association between our job design and nature of work composite measure and wellbeing among the graduate sample.

In the final piece of this section, we look at how our design and nature of work measure is related to occupation type. Although not an indicator of job quality as defined by the MJQWG, one of the other key metrics used in assessing graduate outcomes is whether or not they move into ‘highly skilled’ employment, which is defined as being an occupation that sits within one of three groups (managers, directors and senior officials; professional occupations; associate professional occupations) of the UK 2020 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). As Blyth and Cleminson (2016) note, the reason for this is that it is assumed these occupations require the skills attained through higher education and are also likely to align with graduate career aspirations (i.e. they, in effect, proxy for aspects of the design and nature of work component). We have the opportunity here to explore the degree to which such a presumption holds.

In Figure 4, we see that it is mostly the case that the three occupation categories listed above are associated with higher design and nature of work scores and life evaluations, though jobs within caring, leisure and other service occupations display a value more similar to that observed for managerial and associate professional roles (note that this and the last figure in this section do not display any confidence intervals, as the sample sizes we are working with are large and thus have enabled precise estimates to be produced).

Figure 4: The association between SOC 2020 group (major) and the job design and nature of work composite measure among our graduate sample.

Boccuzzo and Gianecchini (2015) point out that educational and skills mismatch are different concepts. The former relates to an instance where qualifications and job requirements do not match, while the latter is to do with whether skills and abilities are applied within the role. It is also worth noting that educational mismatch is not an indicator of job quality as defined by the MJQWG (underemployment is seen as the difference between actual hours worked and the number of hours an individual would ideally like to work), though skills use is regarded a marker of employment quality. However, previous research by Allen and de Weert (2007) has illustrated that, for UK graduates, the two tend to be related. That is, graduates are more likely to be applying their skills in those jobs where the qualification was deemed necessary or valuable.

The Graduate Outcomes survey asks respondents to indicate whether they believe their qualification was required or an advantage for their role (i.e. the extent of educational mismatch). In the appendix, Table A1 shows how the answer to this question varies by SOC group. Although the general trend is for educational mismatch to be greater for graduates in positions that would not be considered to be ‘highly skilled’, there are a sizeable proportion of jobs (almost 40%) in the managers, directors and senior officials category for which graduates state their qualification was neither needed nor an advantage. Furthermore, a considerable fraction of roles in administrative and secretarial occupations, skilled trades occupations, as well as caring, leisure and other service occupations either required a higher education qualification or benefitted from having one (the percentage is near the 50% mark in all three categories).

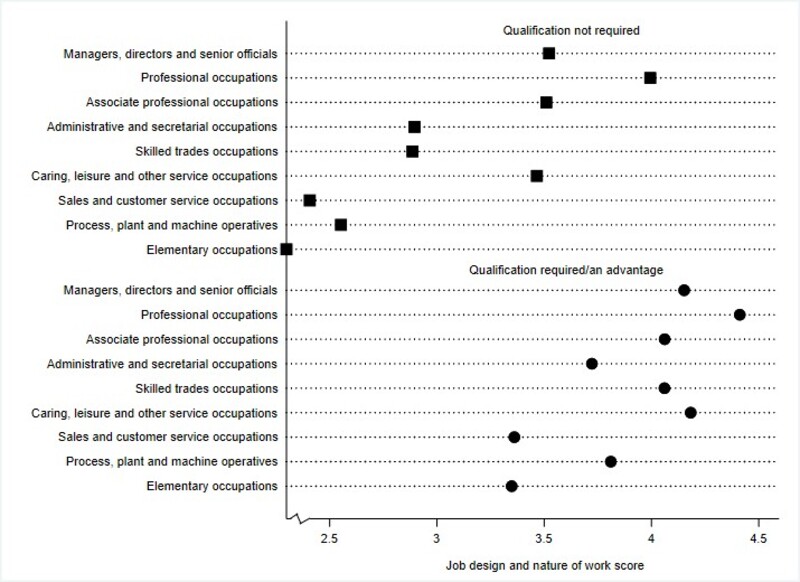

Given the findings reported by Allen and de Weert (2007) on the relationship between educational and skills mismatch, alongside what we see in Table A1, we can further the exploration in Figure 4 by separating the analysis based on whether graduates indicated that their qualification was either a formal requirement or an advantage for the role.

When assessing the association between occupation type and the design and nature of work by educational mismatch (Figure 5), we see far less difference between the nine SOC groups among graduates for whom their qualification was a requirement or advantage. In fact, design and nature of work scores are quite similar for those in four SOC categories in particular (managers, directors and senior officials; associate professional occupations; skilled trades occupations; caring, leisure and other service occupations). We also note that among graduates in managerial or associate professional occupations who report an educational mismatch, scores are lower when compared with those in administrative and secretarial occupations, skilled trades occupations or caring, leisure and other service occupations who state their qualification was needed or beneficial.

Figure 5: The association between SOC 2020 group (major) and the job design and nature of work composite measure among our graduate sample by whether or not the qualification was required or an advantage in the role.

It has historically been the case that employment outcomes of graduates are analysed from the perspective of earnings (an indicator of job quality as defined by the MJQWG). Nationally, as measures of progress begin to look at subjective and wider social outcomes (rather than only remuneration), the finding that early career earnings and wellbeing do not display a clear positive correlation among recent qualifiers from higher education suggests a need to go beyond investigating graduate pay data. Furthermore, though not an indicator of job quality in itself, public debate on graduate outcomes has also looked at whether they attain ‘highly skilled’ work – based solely on the SOC group of their job. While it has been assumed that these ‘highly skilled’ roles are likely to align with their career goals and utilise their skills, analysis of our composite measure shows that there are occupations that would be classified as not being ‘highly skilled’ where graduates do report a high design and nature of work score. This is particularly the case when the qualification was found to be required or an advantage in the job (i.e. there was an educational match). Consequently, these positions do utilise their skills, provide a sense of purpose and align with their career ambitions. Examples can be found in, for instance, teaching and childcare support occupations, as well as caring personal services - both of which fall into caring, leisure and other service occupations. On the other hand, there are also forms of employment deemed to be ‘highly skilled’ where graduates indicate a low value for our composite measure, such as managerial positions in retail and hospitality where the qualification undertaken was not considered as being needed or helpful.

In combination, these results provide evidence in favour of the use of a composite measure on the design and nature of work in the public domain that could support policymakers in better understanding how graduates are faring in the labour market.

Next: Section 5: Decent work for all?

Tej Nathwani

Contents

- Summary

- Abstract

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Data

- 3. Methods

- 4. Associations with wellbeing and employment

- 5. Decent work for all?

- 6. Concluding remarks

- References

- Appendix

Download research paper as PDF