Time to take SOC: Graduate reflections on the design and nature of their work by occupation

HESA researchers explore the relation between graduates' own assessments of their work and the occupational classification of those jobs.

1. Introduction

While analysing the relationship between occupation and earnings is a well-established line of research, examining how the quality of work varies by occupational category remains relatively under-explored, as highlighted in a recent book on this issue by Williams et al. (2020).[1] However, as the concluding section of this publication outlines, assessing and reporting on the association between these two factors can be useful for individuals in making their career choices (e.g. when determining whether their quality of life may be improved by moving into/aspiring towards a new type of work), as well as for policymakers who are trying to meet national ambitions around enhancing working conditions within society. Employers too may be interested in such findings, as they look to address recruitment and/or retention issues among particular occupations within their industry.

Across all four UK nations, the higher education sector places an emphasis on making sure graduates are able to find employment and support economic growth through the effective utilisation of their skills in the workplace. As well as this, there is a desire to see graduates secure work that they find fulfilling and that meets their career aspirations.

Our design and nature of work measure[2] is a composite variable that captures one dimension of fair work. It is based on three questions in the Graduate Outcomes survey relating to the extent to which a graduate:

- believes their work to be meaningful,

- uses the skills they learned in education, and

- fits in with their future plans.[3]

In this insight, we take forward one of the next steps we identified in our December 2021 publication on graduate mobility and this variable[4] by considering how scores for this composite measure vary between the nine major groups of the 2020 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC)[5], while also attempting to explain why we may be observing some of the patterns we see. Indeed, the relationship between SOC and our measure was an area that our data users expressed an interest in during the consultation phase we held in 2021.

In doing so, we aim to inform policymakers in the higher education sector about the kinds of occupations in which graduates find their work to be fulfilling, while also enabling them to deploy the attributes they developed through study and helping them to work towards their career goals. For reasons discussed above, we hope this briefing will also be helpful to students, graduates, career advisors and employers.

2. Why does this matter?

2.1. National policy

The focus on delivering fair work across the economy remains an important concern across all nations. In England, though an Employment Bill was not raised during the Queen’s Speech in May 2021, the current Government did note that they intend to bring forward legislation that addresses the topics raised in the Taylor Review[6] in due course.[7] Following the release of the 2020 ‘Fair work in Scotland’ report by the Fair Work Convention, the Scottish Government launched a consultation designed to assist the present administration with tackling the challenges raised in the publication around providing fair work to all across the country.[8] The 2021 to 2026 Programme for Government in Wales states that one of its objectives is to ‘build an economy based on the principles of fair work’ and to act upon the recommendations made by the Fair Work Commission.[9] The early part of 2020 saw the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive and the circulation of a ‘New Decade, New Approach’, which highlighted the priorities of the devolved government. With respect to employment, the document notes that ‘there will be an enhanced focus within the Programme for Government on creating good jobs and protecting workers rights. The parties agree that access to good jobs, where workers have a voice that provides a level of autonomy, a decent income, security of tenure, satisfying work in the right quantities and decent working conditions, should be integral to public policy’.[10]

2.2. Higher education policy

A shared objective of higher education policy across all parts of the UK is to ensure graduates are able to find employment that provides them with fulfilment and aligns with their aspirations, while also allowing them to contribute their skills effectively within the economy. Hence, in line with national policy, there is an ambition for all graduates to be able to access fair work. For example, one of the strategic objectives of the Office for Students (OfS) in England is for ‘all students, from all backgrounds to progress into employment, further study and fulfilling lives’[11], with the Scottish Funding Council’s (SFC) strategic framework highlighting a similar goal where the aim is for all learners to be equipped to ‘flourish in employment, further study and fulfilling lives’.[12] A core responsibility of the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW) is to help the Welsh higher education sector provide students with an education that gives them the skills they need to meet their personal ambitions and that match the needs of employers.[13] The ‘Graduating to Success’ strategy in Northern Ireland also recognises the role that higher education has to play in helping individuals to maximise their potential and meeting the skill requirements in the economy.[14]

3. Data

To conduct our analysis, we draw upon the first two years of data from the Graduate Outcomes survey, relating to qualifiers from the academic years 2017/18 and 2018/19. As noted in the introduction, the association between SOC and the design/nature of work was highlighted as an area of interest by our data users. Given a key purpose of this work is to meet this demand and advance knowledge across the sector about this topic in doing so, we limit our dataset to those providers that agreed for their data to be utilised for such reasons.[15] We further restrict our sample to UK domiciled full-time first degree graduates whose main activity after graduation was paid work for an employer in the UK.[16] The graduate must also have responded to all three graduate voice questions on work to be included in the investigation. The final sample size available for analysis was 169,690.[17]

4. Results

Here, we present and discuss the results for the whole of the UK. Within the accompanying appendices, we supply additional tables examining the relationship between occupational category and the design/nature of work measure in each of the four nations.[18] The key findings outlined beneath apply in all countries of the UK.[19]

4.1. What are the main trends?

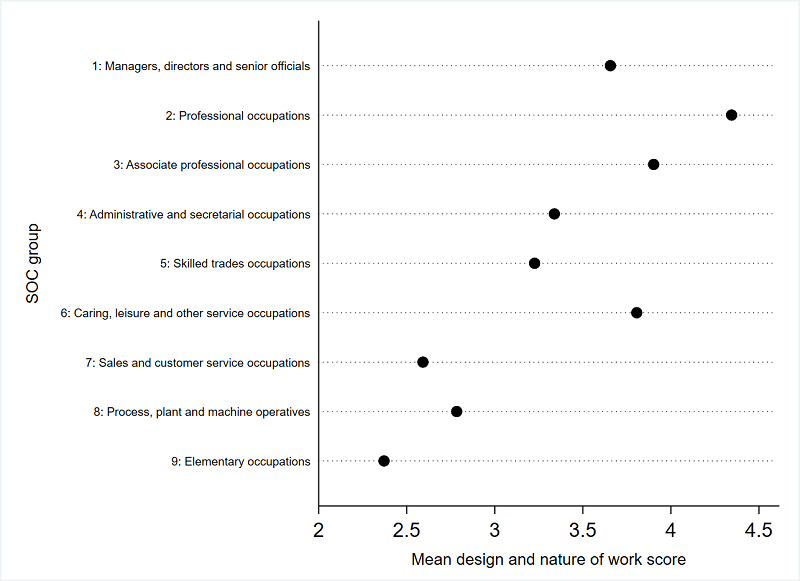

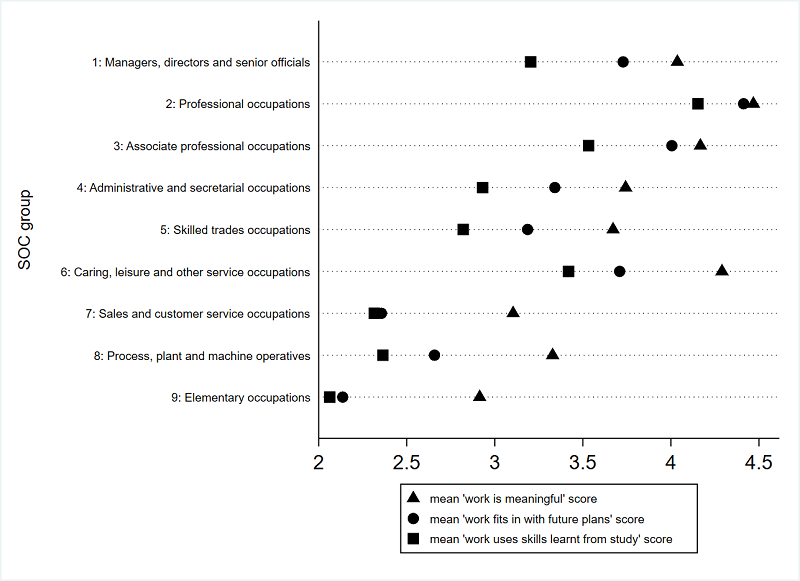

- The score for the composite measure (as well as the individual components that form part of this variable) is particularly high among graduates working in professional occupations.

- Though individuals in managerial/senior roles rate their jobs highly in terms of how meaningful they are, scores are comparatively lower when considering the extent to which they utilise their skills from higher education, which contributes to reducing their overall design and nature of work score.

- Recent evaluations of the care sector have highlighted that it is characterised by low pay and insecure employment terms. We find that those working in caring, leisure or other service occupations do report high scores (relative to the other occupational categories we assess) with regards to the design and nature of their work. This is particularly the result of the scores reported for the extent to which those working in these occupations believe their work to be meaningful. Individuals working in this occupational category are predominantly based in the education or human health and social work industries.[20]

- Comparably low overall scores emerge among graduates employed in sales/customer service roles, elementary occupations and those within the process, plant and machine operative group.

Figure 1: Mean design and nature of work score by SOC group

Figure 2: Graduate voice question scores by SOC group

4.2. Further examination – why might we observe these findings?

Recent research has shown that two determinants of what makes work meaningful to an individual include autonomy over tasks and the opportunity to make a positive impact on the lives of others.[21] With regards to autonomy, in evaluating how occupation ties in with good work, Williams et al. (2020) illustrate how those in professional roles tend to be given more discretion over their duties. This provides more prospect for self-expression and taking responsibility for specific work tasks, resulting in a job becoming increasingly meaningful to the individual. Furthermore, within our sample, we find a large proportion (47%) of graduates in professional occupations work in either education or human health and social work activities – sectors of the economy where employees can often observe the direct impact of the work they carry out on those in society.

Indeed, for those working in caring, leisure and other service occupations, we noted earlier that they also score their jobs especially highly in terms of how meaningful they are. Drawing upon the qualitative interviews reported by the Scottish Government (2019) in a report on fair work in the social care sector and Martela et al. (2021), it is the wider impact that an individual’s work can have on the lives of others within this field that may be driving these high values. In contrast, Williams et al. (2020) illustrate that those employed within sales and elementary occupations tend to be provided with less independence and task ownership in their role, which is perhaps why graduates in such positions report low scores for the extent to which their job is meaningful.

In terms of application of skills, previous work by Elias and Purcell (2013)[22] has demonstrated that professional occupations are also ones that tend to demand knowledge and expertise developed through courses studied in higher education, which may help to explain why we see such a high skill use score among graduates in professional occupations. Indeed, many graduates are likely to have chosen their programme of study with a view to following such career pathways. Conversely – as Elias and Purcell (2013) note - sales, customer service and elementary occupations do not routinely require knowledge or attributes developed through a degree, which is the probable cause of low scores for skills use and career alignment in these categories.

We can also utilise the work of Martela et al. (2021), as well as Elias and Purcell (2013) to understand why those in managerial/director roles may be reporting high scores for the extent to which their job is meaningful, but comparably lower values for skill use. Those in such senior positions will often have a great deal of autonomy in determining the direction for (parts of) an organisation, with such independence contributing to making a job more meaningful. However, their responsibilities will often encompass duties such as assessing risk and devising strategies around which activities can be centred. Becoming proficient in performing these functions will often arise through labour market experience, with such roles not necessarily demanding knowledge or skills gained in higher education.

5. Next steps

It should be noted that this piece focuses on the correlation between SOC 2020 and the design/nature of work, while also offering possible reasons as to why we observe the trends we see. We will also be carrying out an econometric analysis relating to our design and nature of work measure at a later date. However, as in an empirical academic paper, researchers will firstly tend to develop a better understanding of their dataset by examining a range of summary statistics before embarking on such work. We are therefore following a similar approach here by generating these shorter descriptive insights before conducting a more detailed investigation. It should be noted that it would remain the case that we are focusing on correlation/association even if we had undertaken an analysis that controlled for other potential determinants of our outcome measure, with the exploration of causal effects often requiring access to experimental data.

However, this is not the only field where insight is being developed through examining correlation – much of the literature on well-being has also tended to rely on data from surveys. We therefore end this piece with a remark from work by Oswald and Blanchflower on their study regarding international happiness[23]:

‘Much of the considerable knowledge that has been gained is currently at the level of correlation. That does not make it wrong or misleading. But it does mean that, as is often true with observational – rather than experimental – social science, we have to be cautious before we can go from even very strong patterns in the data to judgements about cause-and-effect.’

In the meantime, we would welcome comments and feedback from the sector on whether they would like HESA to carry out further descriptive work on the relationship between SOC and the design/nature of work. This may be, for example, by examining the variation in scores within occupational categories, rather than looking at differences across the nine groups. Please feel free to send these to [email protected].

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Full UK sample

- Appendix 2: Graduates employed in England

- Appendix 3: Graduates employed in Wales

- Appendix 4: Graduates employed in Scotland

- Appendix 5: Graduates employed in Northern Ireland

[3] Please see section 9 of the following report - https://www.hesa.ac.uk/files/Cognitive%20Testing%20Outcomes%20report.pdf - for further information on the results of the cognitive testing of the three graduate voice questions.

[5] Please see this webpage for further information on SOC 2020 - https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/standardo...

[6] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/627671/good-work-taylor-review-modern-working-practices-rg.pdf

[7] https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2021-06-08/debates/FD98F7E0-2697-456B-9841-B36685FA0270/EmploymentRights

[10] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/856998/2020-01-08_a_new_decade__a_new_approach.pdf

[11] https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/measures-of-our-success/outcomes-performance-measures/

[12] http://www.sfc.ac.uk/web/FILES/StrategicFramework/Scottish_Funding_Council_Strategic_Framework_2019-2022_Printable.pdf

[14] https://www.economy-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/del/graduating-to-success-he-strategy-for-ni.pdf

[15] We focus on those providers that agreed for data they had submitted to be used for purposes in category 1 – see https://www.hesa.ac.uk/support/provider-info/subscription/onward-use for further details.

[16] We exclude those domiciled/employed in Guernsey, Jersey or the Isle of Man or those for whom we cannot assign a specific region of domicile/employment in the UK. Additionally, we cannot include those undertaking multiple activities at the time of completing the Graduate Outcomes survey. The reasons for this are explained on page 10-11 of our methodological work.

[17] As in the exploration conducted in the methodological paper released in June 2021, we again find that just over 20% of respondents in our sample of interest were either not eligible or did not respond to all three of the graduate voice questions (further analysis did indicate that eligibility was the predominant reason for this). However, the original and final samples were found to be similar across a range of demographic and course characteristics, as well as for key survey outcomes. The routing for the graduate voice questions has since been altered.

[18] The statistics reported in the appendices include the mean, the lower/upper confidence interval limit (based on the t-distribution) and the sample size. Please note that, although often used as a guide, one cannot definitively conclude that overlapping confidence intervals across two separate categories imply that the differences are not statistically significant. Formal hypothesis testing would be needed to confirm this.

[19] Please note that the overarching findings summarised in section 4.1. do not change if we conduct our analysis separately by year of graduation.

[20] See, for example, the Scottish Government (2019) release at https://www.fairworkconvention.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Fair-Work-in-Scotland%E2%80%99s-Social-Care-Sector-2019.pdf for recent research on fair work in this occupation category.

Tej Nathwani

Siobhan Donnelly

Contents

- Insight

- Appendix 1: Full UK sample

- Appendix 2: Graduates employed in England

- Appendix 3: Graduates employed in Wales

- Appendix 4: Graduates employed in Scotland

- Appendix 5: Graduates employed in Northern Ireland